Pressures after giant impacts

If you were to bury into the ground, on a journey to the center of Earth, the weight of the water, rock and/or metal above you would push down on you and the pressure would increase as you went farther and farther down. By the time you reached the center of the planet the pressure would be 3.6 million times that at the surface (360 gigapascals). But it hasn't always been that high.

In a new study, Sarah Stewart and I have shown that when the Earth first formed, the pressures in Earth could have been less than half what they are today. Want to know why? Read on.

If you want to know more about a particular topic just hit the question marks. ?

<<< This page is a work in progress so check back soon for further updates. >>>

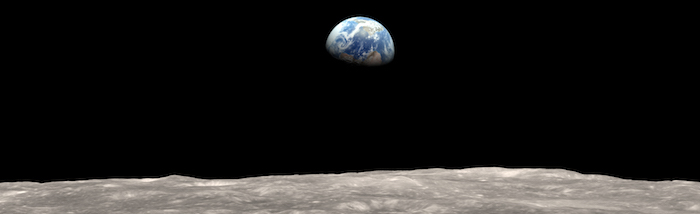

The Moon-forming giant impact

The last event in Earth's accretion was the Moon-forming giant impact. Another planet-sized body smashed into the proto-Earth releasing a huge amount of energy, melting and vaporizing much of Earth's rock, and leaving Earth rotating rapidly. The impact may even have been energetic enough to have transformed Earth into a different type of planetary object, a giant, donut-shaped body called a synestia.

The pressures in the body immediately after the collision are much lower than the present day, in some cases less than half that at the present day ?. The reduction in pressure is due to two factors. The rapid rotation of the post-impact body generates a large centrifugal force, the same force that throws you against the side of a car when going around a traffic circle (roundabout), that acts against gravity to reduce the pressure from the material above a point in the planet. The low density of the hot, partially vaporized body also reduces the weight pressing down, again reducing the pressure on a given parcel of material.

The pressure in the post-impact body is generally lower than in the largest of the colliding bodies even though the post-impact body is typically more massive ?. The increase in mass of the body is offset by the effects of rotation and lower density. Even in cases where the mass of the planet almost doubles, the pressure at the core-mantle boundary can still drop due to the impact.

A new paradigm for pressure changes during formation

The effect of giant impacts on internal pressures is not restricted to Earth. After any giant impact, the pressures in the post-impact body(ies) will be dictated as much by the parameters of the impact as by their mass. Planets of all masses would have their internal pressures changed due to giant impacts.

This is not what had been previously assumed. It had been assumed that the pressures after giant impacts were similar to those in solid, slowly-rotating planets. The pressure in a body would have been only dependent on its mass and composition and would have increased as the planet grew. What we have shown instead is that the pressure in planets varies stochastically in response to every impact. This is a new paradigm for pressure evolution in planets.

But why does it matter?

This new paradigm forces us to reinterpret some of the chemical tracers of planet formation. As the proto-Earth grew, each object that collided with it delivered metal into the mantle. After each impact, the metal absorbed small amounts of other elements from the mantle, and then sank to the core – dragging those elements with it. The amount of each element that dissolved into the metal was determined, in part, by the earth's internal pressures. As such, the chemical composition of the mantle today records the mantle pressure during the planet’s formation.

Studies of the metals in the earth's mantle today indicate that this absorption process occurred at pressures found in the middle of the mantle today. It is often posited that the metal and silicate equilibrated on top of a solid lower mantle before being transported rapidly to the core. However, giant impact models show that such impacts melt most of the mantle, and so the mantle should have recorded a much higher pressure – equivalent to what we now see just above the core. This anomaly between the geochemical observation and physical models is one that scientists have long sought to explain.

By showing that the pressures after giant impacts were lower than previously thought, we can reinterpret the lower-than-expected pressures of equilibration inferred from the geochemistry of the mantle. Earth's core formed in the aftermath of energetic giant impacts that temporarily lowered the internal pressures. This is a very different physical scenario for the formation of terrestrial planets and more work is needed to understand its implications for the chemical structure and subsequent evolution of Earth.

What happens after the impact?

After giant impacts the pressures don't remain constant, they evolve rapidly as the post-impact body cools and any satellites produced recede away from the planet. This gradual increase in pressure leads to previously unrecognized processes that can have a significant impact on planets chemical and physical structures.

The way forward

Press coverage and resources

We are enthusiastic about sharing our work with the public. If you are a writer or a member of the press, and would like to cover our work, please don't hesitate to contact me.

All photos used on this site are either available under a creative commons license, or are the property of Brian Lock or NASA.

For the avid reader

If you want to know more about any particular topic, just hit one of the questions marks. These asides will give you more in-depth information and hopefully a little more food for thought.

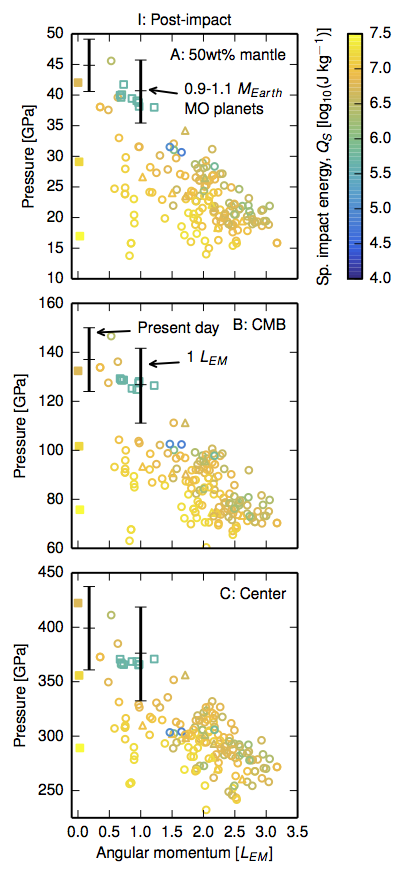

Post-impact pressures

The pressures in post-impact bodies can vary a lot depending on the exact parameters of the impact: the size of the two bodies that collided, the velocity at which they collide, whether they were rotating before the impact etc. These parameters dictate how rapidly rotating the post-impact body is and how much of the body is vaporized, and so the internal pressures.

There are a wide range of possible impact parameters and the produce post-impact bodies with an equally large range in pressure. On the right is a plot of the pressures in the middle of the mantle (top), at the core-mantle boundary (middle), and the center of a range of post-impact bodies 24-48hrs after the initial impact. All the post-impact bodies have masses between 0.9 and 1.1 Earth masses. The black bars give the range of pressures in solid or liquid planets over the same mass range with two different rotational states. The points are colored based on how much energy was released in the impact and, roughly speaking, the higher the energy the more vaporized the post-impact body. The x-axis is angular momentum (think of this as the spin inertia of the body) and, as a rule of thumb, the higher the angular momentum the more rapidly rotating the post-impact body.

The hotter (the higher the energy of the impact) and more rapidly rotating (angular momentum) the lower the pressure in the post-impact body, demonstrating the effects of the centrifugal force and density. The pressures in post-impact bodies are typically much lower than in solid or liquid planets.

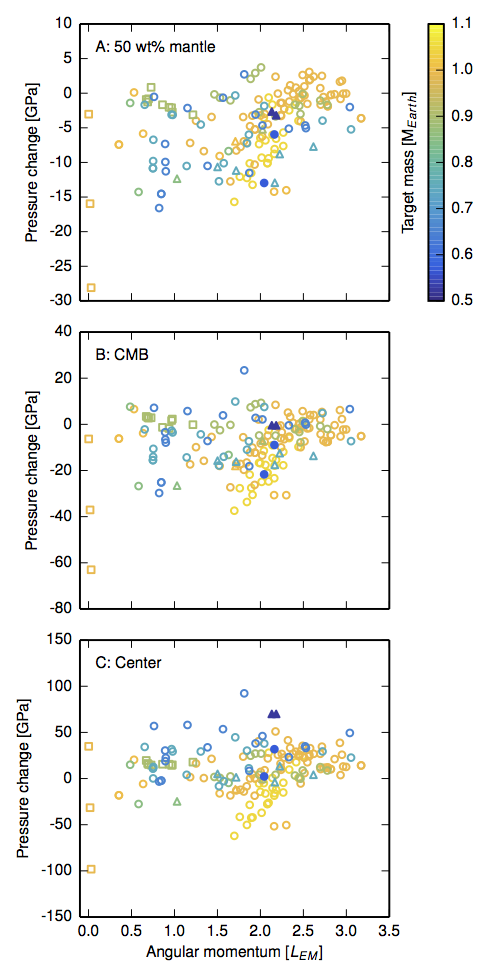

Pressure can go up as well as down

The pressures in post-impact bodies can be lower than the pressures in the largest colliding body, even though the post-impact body is more massive. On the right is a plot of the difference in pressure between the post-impact body and the largest of the colliding bodies. All the post-impact bodies have masses between 0.9 and 1.1 Earth masses. Panels show the pressures in the middle of the mantle (top), at the core-mantle boundary (middle), and the center of the bodies. Colors indicate the mass of the largest of the colliding bodies.

In a lot of cases the effect can be quite counterintuitive. Despite the post-impact body being more massive than either the colliding bodies, the internal pressures can be lower. For example, look at the four dark blue, filled symbols. These post-impact bodies were produced by the collision of two approximately half-Earth mass bodies. Despite almost doubling in mass, the pressure at the core mantle boundary either stayed the same or actually decreased!