Moon formation

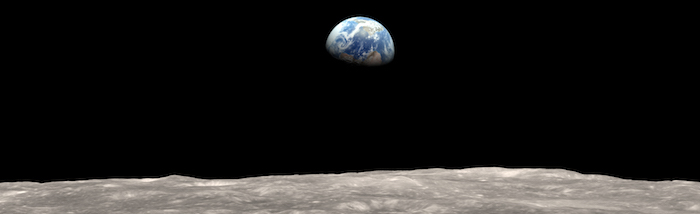

On most nights of the year, you can see the Moon hanging in the night sky. But how did it get there? Why doesn’t every planet in the solar system have its own planetary companion? How did the Moon acquire its unique properties? These are questions I, along with my colleagues, try to answer.

We have recently proposed a new model for lunar formation: that the Moon formed inside the vaporized Earth. Our model can explain various observations of Earth and the Moon for the first time. Continue reading to learn more about why we need a new model and how our model works. If you want to know more about a particular topic just hit the question marks. ?

A preprint of our article can be found on arXiv.

What’s wrong with the old model?

The last stage of the formation of terrestrial planets is marked by collisions between planet-sized bodies. These collisions, known as giant impacts, release a huge amount of energy, melting and vaporizing rock, and can leave a rapidly rotating post-impact body. These impacts have a particular importance for Earth as the last giant impact the Earth experienced is thought to have formed our Moon.

In the canonical model for Moon formation, the proto-Earth was hit by a Mars-mass body in a grazing impact. The impact injected material into a disk around Earth, out of which the Moon formed. This has been the model in text books for twenty years, so what is wrong with it?

In the canonical model for Moon formation, the proto-Earth was hit by a Mars-mass body in a grazing impact. The impact injected material into a disk around Earth, out of which the Moon formed. This has been the model in text books for twenty years, so what is wrong with it?

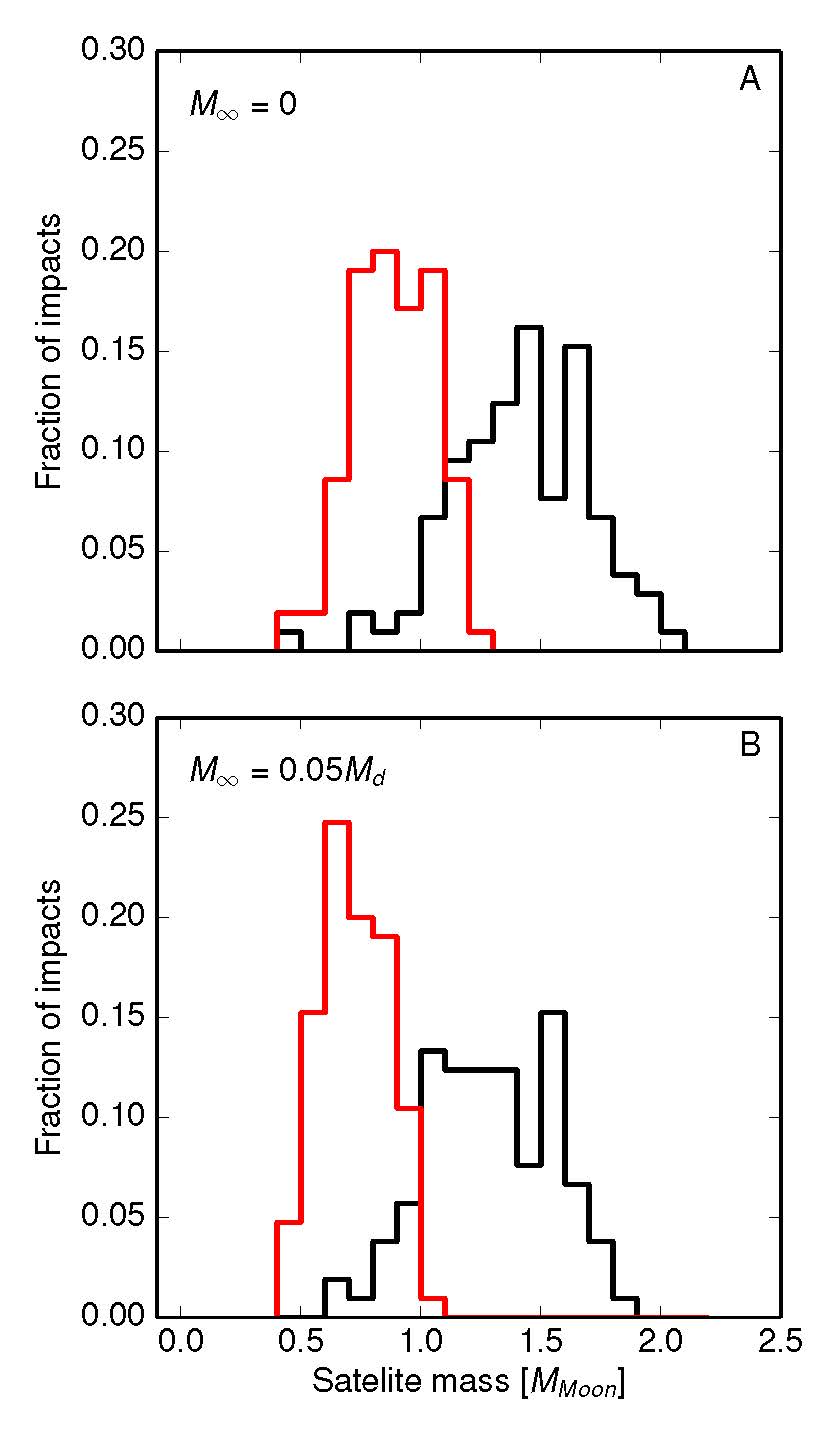

There are some key observations of Earth and the Moon that have proved hard to explain using the canonical model. First, the Moon is a large fraction of the mass of Earth (about 1%) and it is difficult to get enough mass into orbit to form a large enough mass Moon in the canonical impact. ?

Second, the Moon has a similar bulk composition to the Earth, but it is missing large amounts of more volatile elements (ones that are more easily turned into gas). The Moon’s distinctive composition has not been properly explained.

Finally, Earth and the Moon share virtually the same isotopic fingerprint. When we look at meteorites, including those from Mars and large asteroids, we find that each body has a different ratio of isotopes (atoms of the same element that have a different number of neutrons and so slightly different masses) for a variety of different elements. Some of these isotope ratios are controlled by what material the body grew out of, and others are dictated by processes that happen in the body as it forms, such as separating out a metal core. We therefore expect that the body that hit the Earth, often called Theia, would have had a different isotopic fingerprint than the proto-Earth. In the canonical model, most of the mass of the Moon comes from Theia and so the Moon should have a different isotopic fingerprint than Earth, but it doesn’t.

Finally, Earth and the Moon share virtually the same isotopic fingerprint. When we look at meteorites, including those from Mars and large asteroids, we find that each body has a different ratio of isotopes (atoms of the same element that have a different number of neutrons and so slightly different masses) for a variety of different elements. Some of these isotope ratios are controlled by what material the body grew out of, and others are dictated by processes that happen in the body as it forms, such as separating out a metal core. We therefore expect that the body that hit the Earth, often called Theia, would have had a different isotopic fingerprint than the proto-Earth. In the canonical model, most of the mass of the Moon comes from Theia and so the Moon should have a different isotopic fingerprint than Earth, but it doesn’t.

What has changed?

The style of impact that formed the Moon in the canonical model is dictated by a very strong constraint, the angular momentum of the Earth-Moon system. Angular momentum is the spin inertia of a body. The higher the angular momentum of a body, the faster it can rotate and the harder it is to stop the body from rotating. The amount of angular momentum in the universe is constant and is just passed between different objects. In the canonical model, it is assumed that the angular momentum of the Earth-Moon system immediately after the Moon formed was the same as it is today. This assumption limits the velocity of the impact, the mass of the impacting bodies, and the angle at which the two bodies collided. It was found that only a grazing impact with a Mars-mass impactor at near the escape velocity can put enough mass into orbit to potentially form a lunar-mass moon. This is why the canonical model is such a specific type of impact.

However, the angular momentum constraint might not be as strong as we thought. The angular momentum of the Earth-Moon system could have been reduced over time by competition between the gravitational pull of Earth, the Moon and the Sun. ? The impact that formed the Moon could therefore have been one of a much larger range of collisions.

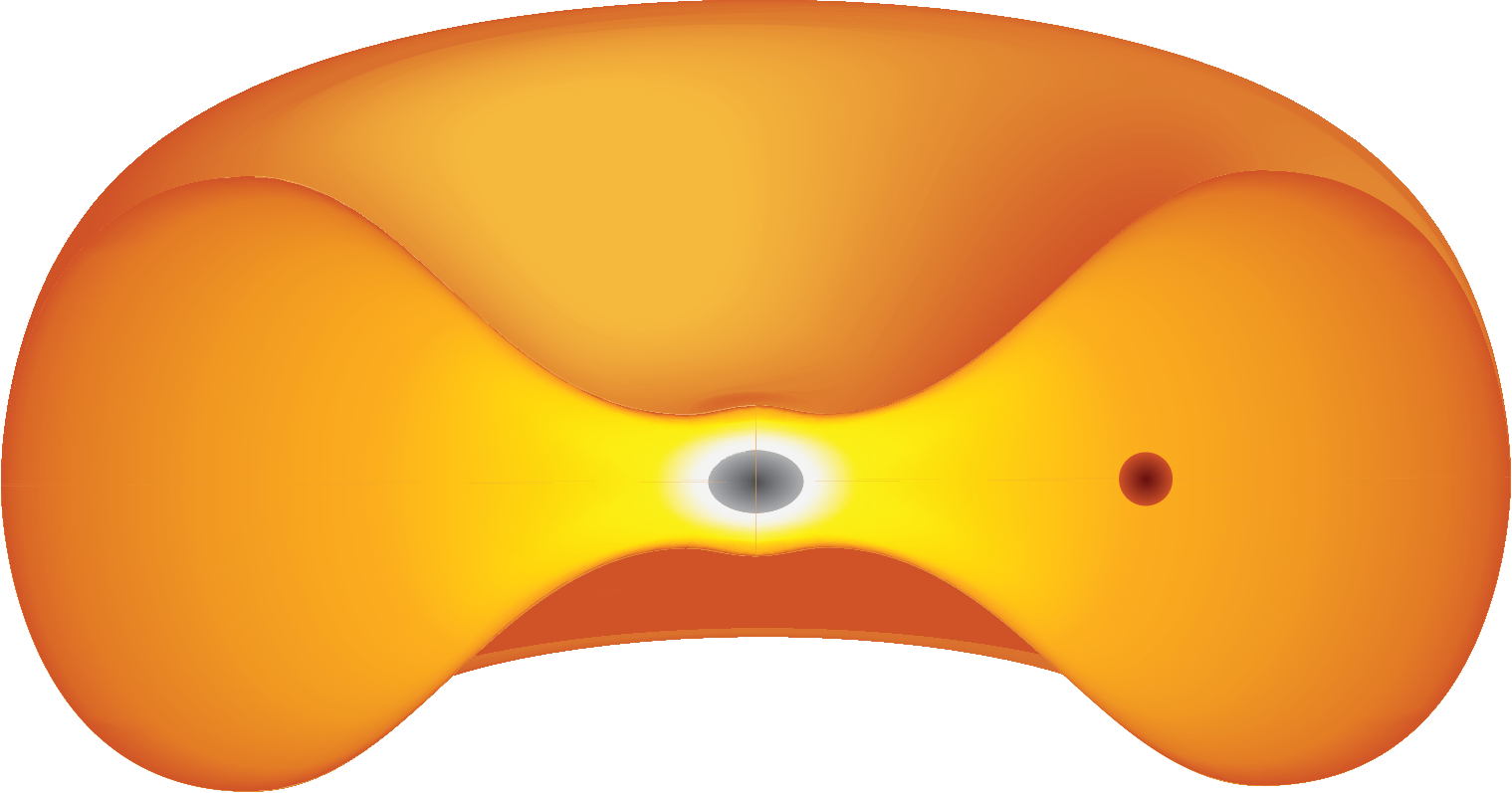

The Moon-forming collision could have been much more energetic than the canonical impact. Sarah Stewart and I have shown that such high-energy, high-angular momentum impacts can produce a different type of planetary object, synestias. High-energy impacts vaporize a substantial fraction (10% or so) of the rock of the impacting bodies and the resulting synestias can be huge, with equatorial radii of more than ten times that of the present-day Earth. For more about synestias see here. Synestias are a very different post-impact body to a canonical planet and disk.

How does a synestia change how the Moon formed?

Because the impact-produced synestia was so big, the Moon formed inside the vapor of the synestia surrounded by gas at pressures of tens of bars and temperatures of 3000-4000K (4000-6000 F). Fragments of molten rock from the impact collided together and formed a lunar seed orbiting within the vapor of the synestia. The surface of the synestia was hot (2300 K) and the body cooled rapidly. The loss of energy led to the condensation of rock droplets at the surface of the synestia, and a torrential rock rain, ten times the rain rate in a hurricane on Earth, fell towards the center of the synestia. Some of this rain was revaporized in the hot vapor of the synestia, but some encountered the lunar seed, and the Moon grew.

Below is a movie of one our simulations, showing a cross-section of the pressure field inside the synestia as it cools. The black circle shows the size and position of the Moon within the structure. The right hand side shows the mass of the Moon growing over time.

As the synestia cooled, more of the vapor condensed and the body contracted rapidly. After ten years or so, the synestia shrank inside the orbit of the Moon and the nearly fully-formed Moon emerged from the vapor of the synestia. The synestia continued to cool and became a planet within a thousand years or so of the Moon emerging from the structure.

How does this model help?

Without the tight constraint of the angular momentum, impacts that form synestias can put a lot more mass into the outer regions of the synestia than can be put into the disk in the canonical impact. This makes forming a large, lunar-mass Moon much easier. We have found several synestias that have the potential to form a lunar-mass Moon.

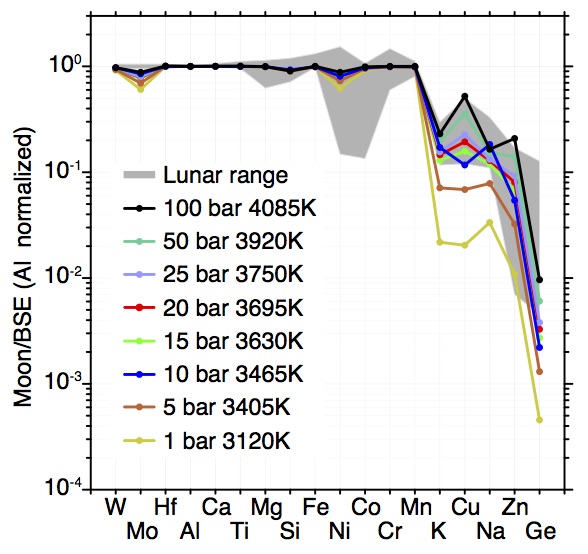

But our model does more than help explain the large mass of the Moon. Because the Moon formed within the synestia, surrounded by hot vapor, it inherited its composition from Earth but only retained the elements that are more difficult to vaporize. The more volatile elements remained in the vapor of the synestia. When the synestia cooled and contracted inside the Moon’s orbit, it took all the more volatile elements with it. We have shown that the pressures and temperatures at which the Moon would have formed inside the synestia would give it a composition similar to that observed in our Moon. Ours is the first model to be able to quantitatively explain the Moon’s composition. ?

But our model does more than help explain the large mass of the Moon. Because the Moon formed within the synestia, surrounded by hot vapor, it inherited its composition from Earth but only retained the elements that are more difficult to vaporize. The more volatile elements remained in the vapor of the synestia. When the synestia cooled and contracted inside the Moon’s orbit, it took all the more volatile elements with it. We have shown that the pressures and temperatures at which the Moon would have formed inside the synestia would give it a composition similar to that observed in our Moon. Ours is the first model to be able to quantitatively explain the Moon’s composition. ?

Our model can also help explain the isotopic similarity between Earth and the Moon. The Moon inherited its isotopic fingerprint from the vapor that surrounded it in the outer regions of the synestia. The outer regions of the synestia can represent a large mass fraction (tens of percent) of the rock of the body. Energetic impacts that form synestias tend to efficiently mix material from the two colliding bodies, and the outer portions of the synestia in which the Moon formed would have had an isotopic composition that was similar to the rest of the synestia. Earth and the Moon therefore share a similar isotopic fingerprint which is made by a mixture of the isotopic compositions of both the bodies that collided.

The way forward

Our model changes the focus of the study of Moon formation. The key component of our model is the synestia that was formed by the impact, and there are many possible impacts that could form a suitable synestia. The focus of further research will be the properties of a synestia that are required to form the Moon, not a specific impact.

Our model changes the focus of the study of Moon formation. The key component of our model is the synestia that was formed by the impact, and there are many possible impacts that could form a suitable synestia. The focus of further research will be the properties of a synestia that are required to form the Moon, not a specific impact.

The study of forming Moon-formation from a synestia is still in the preliminary stages. We have shown that each of the steps to form the Moon from the synestia are feasible, but there is a lot more detailed interrogation of each of these steps yet to do. Also, by better constraining the chemical and isotopic composition of Earth and the Moon, we can find new tests of our model to see whether it truly can produce a Moon that looks like our own.

Want to know more?

If you want to know more about how the Moon could have formed from a synestia, you can find the full journal article here. A preprint of the article can be found on arXiv.

Press coverage and resources

Our work have been covered by a number of different news outlets. Below is a selection of different articles.

We are enthusiastic about sharing our work with the public. If you are a writer or a member of the press, and would like to cover our work, below are a number of resources. Please don't hesitate to contact me if you have any questions.